We woke up in Nasca — a decent little town in the northern part of the Atacama desert in southern Peru. It was founded by Viceroy Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza in 1591.

After breakfast, we relaxed a little bit as Felix was still ill. Then, Gisela and Felix went shopping while I covered the cultural part, and visited the archaeological museum Antonini.

Antonini Didactic Museum

The museum houses a collection of musical instruments, textiles, mummies, ceramics, and trophy heads of the Nascas. Trophy heads are human skulls that have a hole punched in the forehead to which a rope is affixed. Probably, these ropes allowed the head to be carried or to be displayed. The scientific community still debates if these heads are war trophies of decapitated enemies or ritual objects of unfortunate victims of human sacrifices.

The museum also tries to capture their daily lives, and displays their diet, as well as information about the region, and the climate. Most of artefacts were discovered as part of excavations in Cahuáchi, a former cultural centre of the Nascas that is located about 30 km west of the city of Nasca.

A sophisticated irrigation system that was the basis for the steady food supply of the Nascas is explained as well.

The Nascas

The Nasca culture developed around 100 BC and ceased around 750 AD.

The Nasca lived in several local chiefdoms that were not centrally administered by a king or ruler. The policy makers were probably a caste of shamans.

The discovery of precious

Initially, the the climate was subtropical and humid enough to support grassland which provided the Nasca with an excess of food. Archaeologists suggest the collapse of the Nasca culture to be a result of a drier climate that lead to food and water shortages, and to karst formations of the once fertile soil. Left with the choice to stay and starve or to move, the Nascas decided to relocate to more humid areas.

Generally, the time of the Nasca is broken down into 7 phases:

| Phase Name | Phase | Time Range |

|---|---|---|

| Proto Nazca | 1 | 100 BC – 1 AD |

| Early Nazca | 2,3,4 | 1 AD – 450 AD |

| Middle Nasca | 5 | 450 AD - 550 AD |

| Late Nasca | 6,7 | 550 AD –750 AD |

TV documentary about the Nascas — unfortunately in German only

Maria Reiche Planetarium

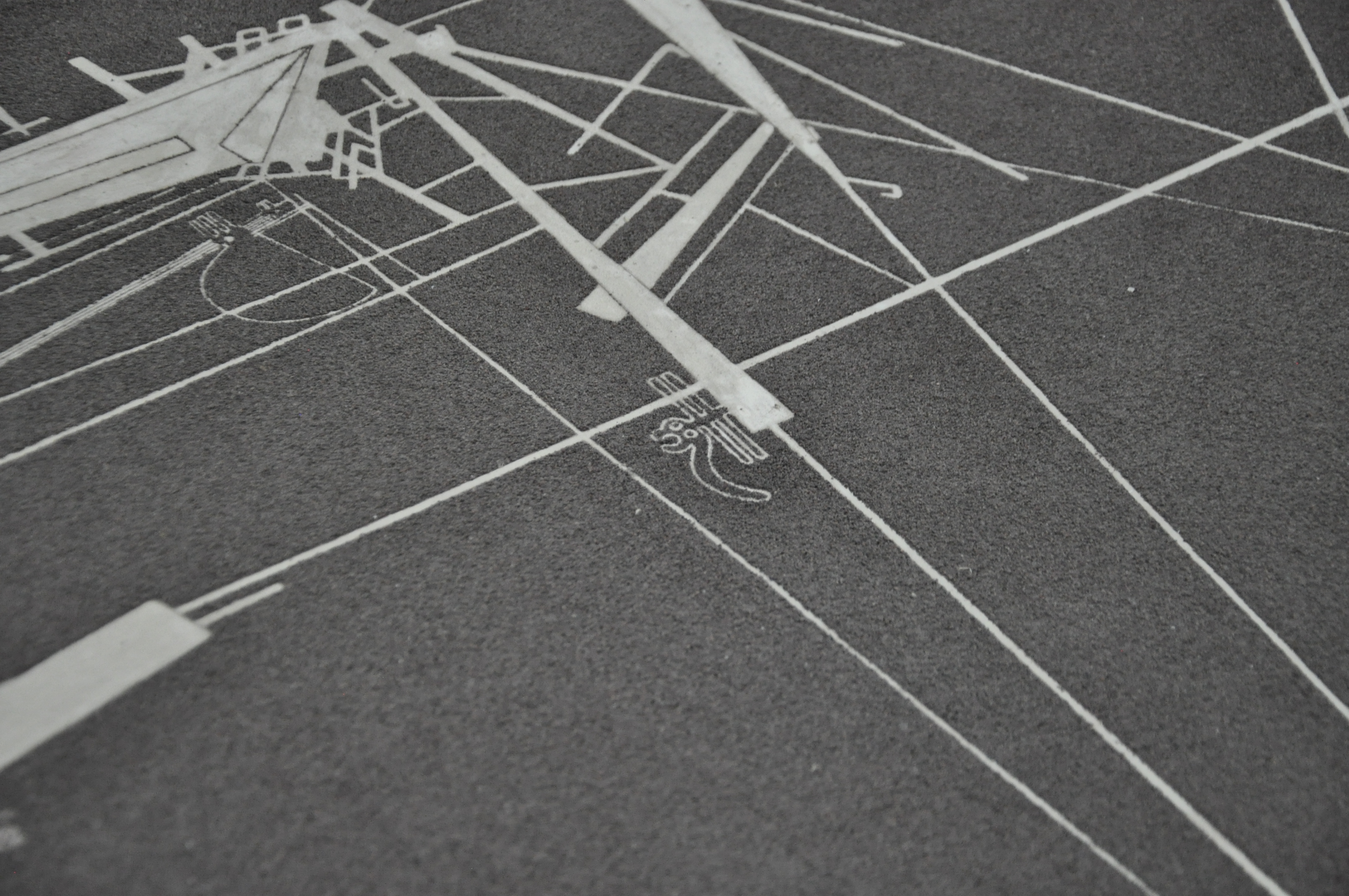

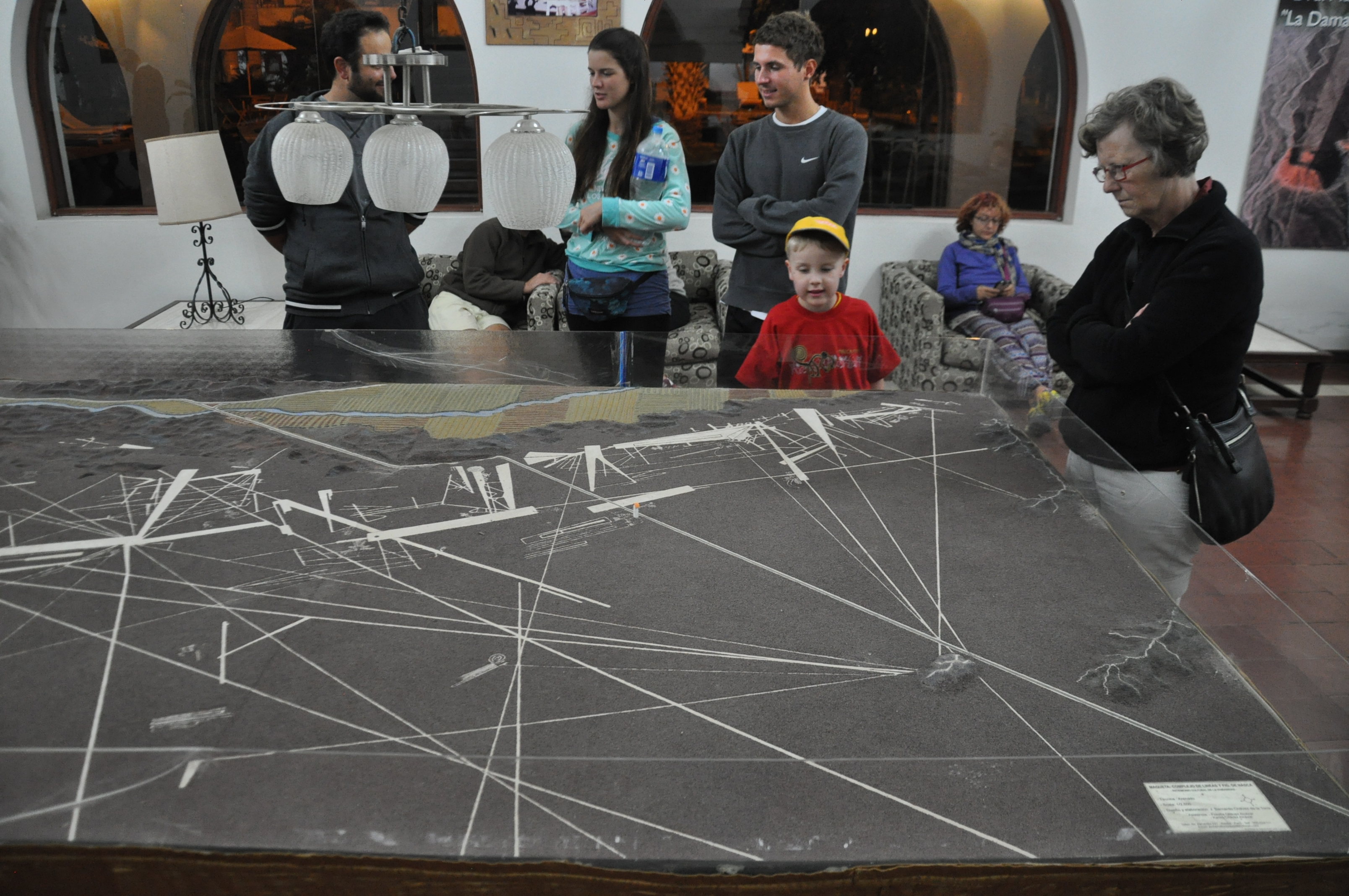

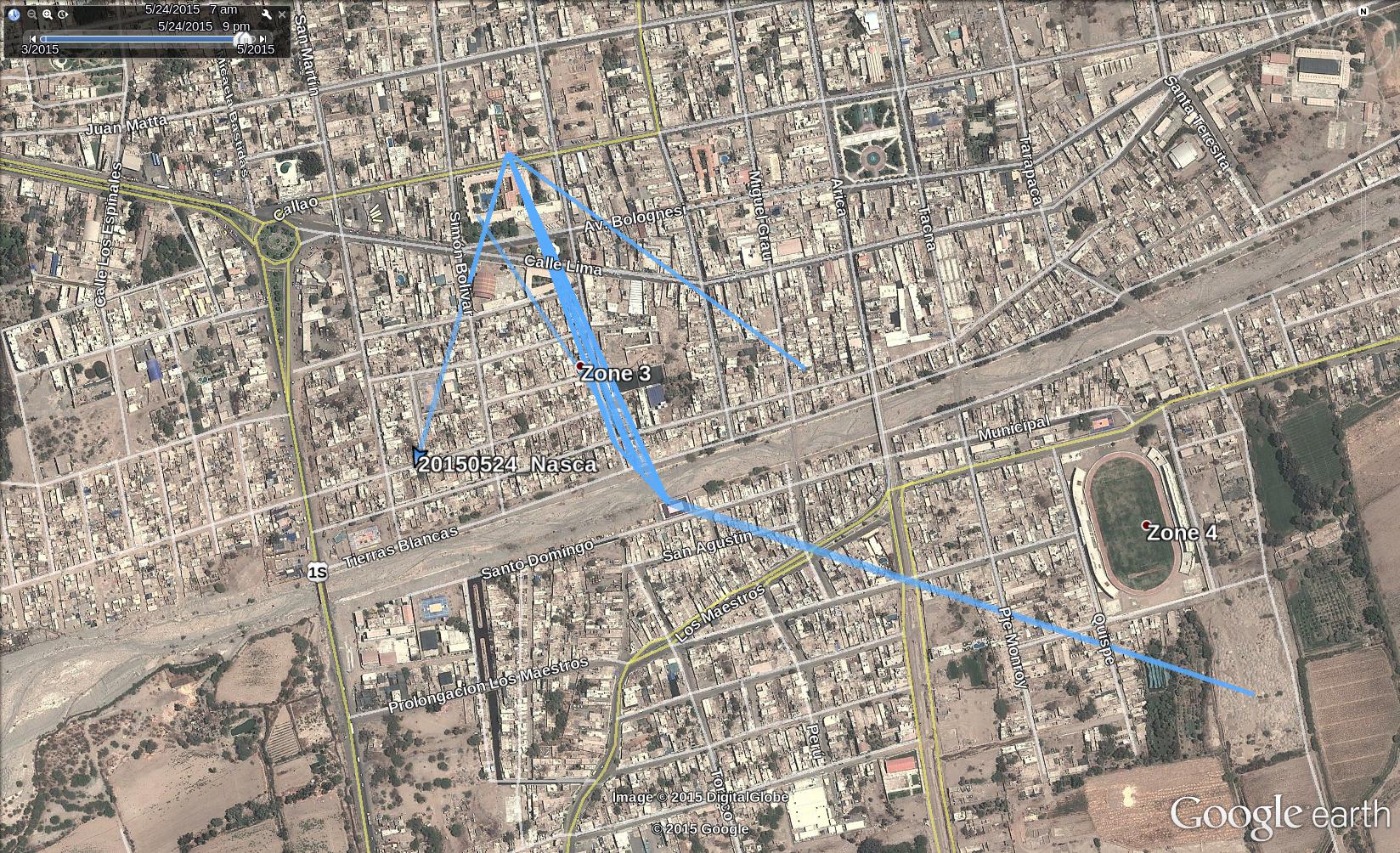

The planetarium, a small building with a dome, is actually on the premises of the Nasca Line Hotel at which we stayed. It features a multimedia show of the sky over Nasca, i.e. the star, planets, and constellations, and then goes on explaining the theories of the archaeologist and mathematician Maria Reiche. She believed the Nasca lines to be aligned in relationship to the stars. After seeing the show, we were invited to step outside and to watch the moon through a telescope. As the distance moon – earth is shortest near the equator, the moon appears to be bigger than in Europe. A nice show, and one can really see the effort, the heart and soil the volunteers running the planetarium are pouring into the project. The projectors displaying the stars and the Nasca Lines on the inside of dome for instance, are actually home build.

Maria Reiche

Maria Reiche was an archaeologist and mathematician who researched, mapped, and made the Nasca Lines known to the world starting from 1946. She was born in 1903 in Dresden/Germany, and emigrated to Lima in 1932 working as a tutor for the German consul in Cusco. In 1939, she learned about the Nasca Lines, when she became an assistant for Paul Kosak, an American scientist. He asked her to do measurements of the lines for him which he believed to be an astronomical calender that governed the yearly sowing and harvesting. Living a Spartan life in the desert, and supported only by herself and her partner Amy Meredith from Lima, she devoted the rest of her live to the research, cleaning, and preservation of the Nasca Lines. She believed that the lines were used as sun calender and as an observatory marking astronomical cycles. Today, it is widely accepted that the Nasca Lines supported religious ceremonies and were actually used as procession streets.

In 1978, she succeeded in persuading the Peruvian government to put the lines under protection and to forbid trespassing that started destroying the lines. Due to her intervention, the UNESCO declared the lines and geoglyphs a world heritage site in 1994. If it wasn’t for her, the Nasca lines would be largely unknown, and not many tourist would find their way to Nasca.

Late in her live, the Peruvian government finally recognized her achievements, and granted her the Peruvian citizenship. Once her health deteriorated, and she was no longer fit to live a basic life in the desert, she received free lodging in the Nasca Line Hotel for the rest of her life. The flat she occupied is still there, and is preserved in the state in which she left it. She died in 1998 from ovarian cancer in Lima, and is buried next to the hut near Nasca where she lived for more than 25 years.